|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State of the Industry

Texas milk production shifts west, continues upward climb

Editor’s note: As part of our “State of the Industry” series we take a look at the cheese and dairy industry across the United States. Each month we examine a different state or region, looking at key facts and evaluating areas of growth, challenges and recent innovations. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest state — Texas.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — Texans tend to do things in a big way, and the Texas dairy industry is no exception. Currently Texas ranks sixth in the nation’s milk production, and it consistently is one of the fastest growing states. The average herd size has reached more than 600, and with a recent boom in the northwest panhandle and dairies continuing to expand and relocate from out of state, Texas is poised to continue its upward climb.

|

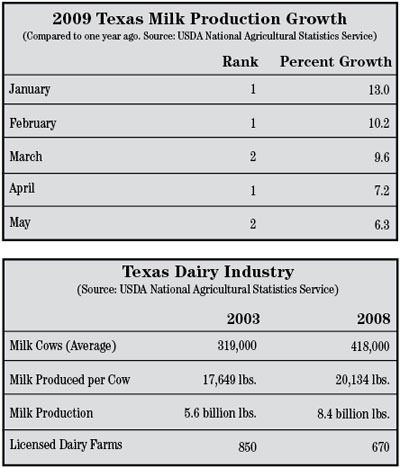

| MORE COWS, MORE MILK — While dairy farms in Texas have declined over the past several decades, cow numbers and milk production have grown at a rapid pace during the last five years. |

Todd Bilby, associate professor and extension dairy specialist, Texas A&M. “In the last five years it’s really exploded.”

The Texas dairy industry started out small, with cows kept mostly for subsistence to milk and make cheese and butter at home through most of the 19th century, according to the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). After the Civil War, most of the cheese consumed in Texas came from the former dairy belt that stretched from New York to Wisconsin. As cities grew larger, more manufacturing developed, and by 1900, 12 creameries were operating in Texas. By 1914, the state had about 100 creameries producing more than 5 million pounds of butter a year, and in 1939, 228 dairy product plants were operating in Texas.

Like much of the country, the Texas dairy industry experienced dramatic changes following World War II, including milk price wars and a sharp decline in the number of milk cows. The state went from almost 1.6 million milk cows in 1945 to 355,000 in 1971, followed by continued decline at a much slower pace, according to TSHA. However, the release of millions of acres of land that had been devoted to cotton between 1930-1940 helped to stimulate dairy production again, and new, more efficient practices emerged from the growth of large, specialized dairy farms. Milk cows and production grew in Texas through the 1980s.

After another brief period of decline during the mid to late 1990s, the growth spurt over the past several years has helped raise the number of milk cows in Texas from 317,000 in 2002 to 418,000 in 2008, and milk production from 5.3 billion to 8.4 billion over the same six years, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Part of the reason for this increase has been the number of dairy farms that relocated to Texas from other states, particularly farmers from western states like Arizona and California seeking more land and a dairy-friendly environment.

“Land was cheap — they could sell it out in California by the square foot, come out here, and buy a lot more,” Bilby says. “Texas is still a very ag friendly state as well, and California was running into issues where it was not so ag friendly.”

Growth and transition also came from within the state. In the 1980s, milk production was concentrated in the eastern part of Texas, with more than 90 percent produced east of a line from Wichita Falls through Brownwood, San Antonio and Corpus Christi, according to TSHA. However, as metropolitan areas like Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth continue to grow, the state’s dairy production has moved westward.

As Texas dairy farmers begin to retire with no one to pass the farm to, they have found it profitable to turn their farms into ranchettes and sell to people who want to live near the country and commute into cities and suburbs. Farmers wanting to grow their dairy herds also have found it more advantageous to sell their land in the east and move west, where there is more space and a growing number of processors.

Most of the recent growth in the dairy industry has been west of Interstate 35 and north of Interstate 20, which intersect at Dallas/Fort Worth, according to John Cowan, executive director of the Texas Association of Dairymen (TAD), a trade association that represents the state’s dairy cooperatives as well as individual farmer members.

TAD serves as an advocate for the Texas dairy industry in legislative matters including environmental, regulatory and animal health welfare issues. With increasing urban encroachment, TAD also helps to educate dairy farmers about property rights and educate neighbors to understand more about agricultural and dairy operations.

“If you look at the last 20 years, there has been quite a bit of growth in the west and declining production in the east,” Cowan says. “I think we will continue to see that transition occur.”

Cowan also says there still is plenty of room for dairies to move in from out of state. Even with increasing production, Texas still is a milk deficit state as well as a standby supply pool for other states. Much of the milk produced in Texas is transported to help fill shelves in the Southeast part of the United States. About half of the milk produced in Texas goes toward Class I utilization.

“There’s a lot of support in Texas for dairy farmers,” Cowan says. “There are a number of efforts by communities across the state to recruit dairies. It has slowed down considerably because of the recession, but we still have a lot of room for dairies to come to Texas.”

The dry climate, land availability and markets are some of the key draws for dairy farmers coming to the state.

“Texas has a good climate and cattle milk well here,” Cowan says. “We are a big state, with a lot of space between people. The land prices are relatively affordable compared to where most of them came from. We have good markets and a good infrastructure to take care of those who farm and handle their milk.”

In addition to dairy farmers, dairy processors also have been drawn to Texas. In 2007, California-based Hilmar Cheese Co. opened a new 200,000-square-foot plant in Dalhart, Texas, that processes Cheddar, Monterey Jack, Colby, Colby Jack, milled Cheddar and whey protein concentrate. The plant has the capacity to process 5 million pounds of milk per day.

“They saw the opportunity to come into Texas and enjoy (being near) the dairy families,” Cowan says, adding that the Hilmar facility in Dalhart is a dedicated cheese plant, meaning the company already has a market for its product.

Other dairy companies and cooperatives also have a large presence in Texas. Dallas is home to the Dean Foods headquarters, and the cooperative Lone Star Milk Producers Inc. is based in Windthorst, Texas. Other cooperatives that serve Texas dairy farmers include Dairy Farmers of America, which has an office in Grapevine, Texas; and Select Milk Producers and Zia Milk Producers, both based in southeastern New Mexico.

“We’re still, being a very strong ag-friendly state with a milk market and feed availability, poised to be one of the top growing states,” Bilby says. “I think this is a great place to milk animals.”

Cowan says TAD’s ongoing challenge is to do everything it can to enhance the ability for dairy farmers to stay in business and continue to produce safe wholesome products for Texas citizens.

“I continue to believe (the Texas dairy industry) is going to be a very viable, thriving business for a long time,” he says.

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2024 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090